In the first half of her story, Erina Cho (MOT 2020) offered tips to graduating students for making the most of the start of their careers as OTs. In this instalment, she delves into the nitty-gritty of adapting to the constant changes inherent to clinical work, maintaining healthy expectations of herself, and having the courage to ask for help when she needs it.

Earlier, you shared advice for students entering the field. What are some things you wish you yourself had known at the start of your career?

I wish I’d known how hard it was going to be. I felt prepared, I had good preceptors, I was confident, and I thought I knew what to expect: I figured it was just ADLs, but there’s so much more to learn. I had to be gentle with myself; it’s easy to stay late and work beyond your hours—you feel slow, incompetent, and inefficient in your work. You need to learn to set good boundaries, not push yourself too much, and practise self-care so you can be there the next day for your patients and your team.

The first four months were really difficult. In acute care, the unit you work on is often assigned, so you don’t necessarily know where you’re going to be working in the hospital; as soon as I started to get comfortable, they’d move me to another unit. I like having routine and knowing what I’m doing, so it was hard kind of getting into a rhythm and then having to start from scratch all over again. There’s also a lot of lot of turnover in acute care, so you end up working with different types of people.

Change is constant, and, if I’d recognized that a little bit sooner, the transition into clinical care would probably have felt a bit smoother.

What have some of the highs and lows of clinical practice been?

The lows? Well, the pandemic, the systems-level challenges to provide consistent quality of care in acute care, and the tragedies on the front line: losing patients and breaking the news to families. Acute care can feel emotionally heavy at times and not exactly the calmest setting, to say the least. Inpatient rehab isn’t all rainbows and butterflies either, but there is bit more optimism, which was a welcome change for me.

Acute care has its highs too, though. One of the highs has been giving patients a sliver of dignity during their most difficult times—as an OT, you create the change and advocate for your patients. I felt intimidated to speak out at first, but I found out that you really do have a voice and your interdisciplinary team members will usually value your input. You can make a strong case to ensure your patients get good-quality care, and facilitate their transition at discharge so it goes as smoothly as possible for your patients and their families.

I’ve come to realize that the small things often make the biggest differences. Beyond assessing and treating, it can be something as simple as making sure they get their glass of water, bringing them clean socks, or listening for those extra few minutes and validating their experience. These little things might seem insignificant, but I think patients do notice and appreciate these things. And in rehab, you get to work with the same patients for longer—anywhere from two weeks to three months—so you really get to know them and develop a deeper relationship, which is pretty special.

There’s a lot of other stuff—it’s fast-paced, and there are heavy caseloads—so you need to set boundaries and prioritize what you’re going to focus on. You have to define your role, because it’s not uncommon to get referrals that aren’t always appropriate. Also, if you want specific clinical opportunities, don’t be shy and ask. For me, I was interested in working in with the neurology population, but I had to mention it or else no one would have known my personal clinical and career interests. If your colleagues are having a tough few weeks and morale is down, initiate creative ways to make team bonding and peer support a department priority (a few of us started a “mental health” drawer filled with sweets, for a quick cheer-up on those harder days). There’s so much room for what OT can be that you have to find the niche that you can fill and create your own role.

Another recent graduate emphasized the importance of self-care. What do you think enables you to thrive in your profession?

Everyone’s self-care looks a bit different. We always tell our patients to strive for occupational balance, but we don’t always practise it ourselves. I reached a tipping point where I realized I wasn’t practising what I was preaching, and I had to take a step back. Remember your mental health—like the framework we learned in first year—and reevaluate how much your battery is charged and how much it’s depleted. You learn to leave work at work, that some stuff can wait until the next day, and not to take on more than you can finish.

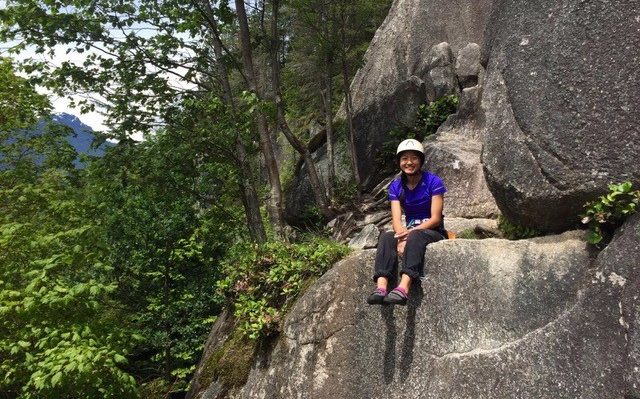

This might sound basic, but making sure you’re eating, sleeping, and exercising is really important. Because so many things have been closed during the pandemic, I recently started looking for a new hobby, and I took up climbing. I made some new friends in physio, and I climb with one of them after work.

Making friends at work was a real game-changer for me. You have to make it a more social setting so you’re not just working on your own all day. In the program, that’s handed to you, because you’re always in class together, but in the workplace you have to create that environment. I joined the social and educational committees—it’s not going to happen if you don’t take the initiative—and now I feel much more at home. You get to know people, and they get to know you; I take a walk every lunch break with a few coworkers to sort of break up the day. It’s good to remind yourself that you have a life outside of work. You have to make time for your hobbies, friends, and family, or you end up in this cycle of just working, sleeping, and preparing for work.

Again, it’ so important to set good boundaries. I often noticed that my peers were leaving at 4:00, and I was still there at 5:00. I’m kind of a perfectionist; I want to do things exactly how I envision them, and it’s frustrating to come up with the best possible intervention for a patient and not be able to do it because I don’t have the time or resources for it. In those situations, I have to compromise and remind myself that it can wait until tomorrow. We often care too much and get—I don’t want to say ‘burned out,’ but kind of jaded. You have to be good to yourself so that you can be good to others.

Brace yourself, because it’s going to be rocky and scary at first, but it’ll be just fine.

Do you have any parting advice for future OTs?

If someone told you that it’s going to be easy, it’s false. I feel lucky being an occupational therapist, though—you get to help people in their transitions in life and help them make small changes to do the occupations they love. Working in public health isn’t for everyone, but if you are interested, here’s a side note: they do tend to hire slower than private practice and can be bureaucratic, so do keep that in mind. I heard back from them two months after applying, whereas several private clinics had recruited me before I’d even graduated. Since I wanted to work in public health, I eventually emailed the CPL (clinical practice leader) directly, and then I heard back relatively quickly. All in all though, I didn’t have confirmation until two days before I graduated.

My advice would be to apply to a whole bunch of places, reapply if you don’t get in the first time, and don’t be afraid to switch jobs. You don’t have to go straight into, say, paediatrics even if that’s what you’ve wanted to do all along; some areas are more popular than others, so it can be hard to find openings, and it helps to just build experience in a variety of areas. I treated my first few jobs—not as placements, obviously, but almost like another placement in terms of keeping an open mind.

Another thing is to be open to feedback. It depends on the site, but not everyone fully understands or appreciates your role. Others can come across blunt, and you might get some harsh comments from time to time – from other staff or patients and their families. You need to find a way both to make use of them and not to let them get you down, while maintaining the perspective that it’s not necessarily you or anything you’ve done. In the program, everyone was so supportive, and we had such gentle, empathetic preceptors. Be patient, because it’s so easy to be hard on yourself.

It might not be obvious, but I do genuinely love my job and my career; I’m happy that I chose OT. It’s a really great profession, and it gets better over time. My initial illusion was that all OTs had perfect work-life balance and that they’re all superhuman. Now I know that we’re all just people and we all have to work hard to keep our occupational balance.

It takes strength to admit that you have struggled at times, especially when you feel that it is your job to help others; while life as an OT is incredibly rewarding, there will inevitably be some bumps in the road. How do you overcome challenges in your daily occupations, and what expectations do you put on yourself? Our next instalments in the Student Series explore the experiences of other recent graduates and offer creative strategies for adapting to a major transition in life. Stay tuned!